Search

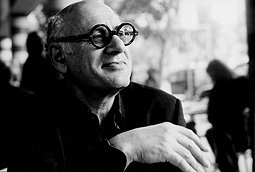

Toby Venables reports on Michael Nyman at Cambridge Film Festival – West Road Concert Hall, Cambridge 3 July 2007

Few can be better qualified to tackle this brief than composer Michael Nyman (and congratulations must go to Cambridge Film Festival for continuing to attract guests of this calibre). It was the score for Peter Greenaway's breakthrough feature The Draughtsman's Contract that first brought him to a worldwide audience, with its carefully balanced blend of Baroque wit and contemporary minimalism cleverly evoking the period without ever falling into pastiche. There followed collaborations with a veritable who's who of art house directors, including Michael Winterbottom, Neil Jordan, Jane Campion, plus, of course, the long and fruitful relationship with Greenaway. But it was for Campion that he was to provide his most famous piece - The Heart Asks Pleasure First, a solo piano work from her film The Piano. Another pseudo-historical score, it combined Nyman's ongoing arpeggio obsession with Scottish folk tunes to create a very individual take on 19th century Romantic music - and also his first (and possibly only) popular hit.

An insanely rain-lashed evening at West Road saw Nyman once again on solo piano - but this time providing accompaniment to cinema of a very different kind. The programme consisted of two silent films, the Soviet newsreel Kino Pravda 21 by Dziga Vertov and Jean Vigo's quirky, surreal and rather saucy seaside travelogue A Propos de Nice (itself influenced by Vertov).

Vertov's Kino Pravda 21 is a grim and serious work celebrating the achievements of Lenin, and culminating with the nationwide mourning surrounding his lying in state. Entirely eschewing the Wagnerian approach to film music (in which the music describes, comments on or anticipates the drama) Nyman's score instead established a textured backdrop against which the drama played, using driving, repetitive rhythms and short, simple themes that neither celebrated nor denounced the film's subject matter. It can be tough to pull off when the music actively resists close involvement with what is seen on screen, but this careful balancing act created moods that at once harmonised with Vertov's often startling imagery, while fully acknowledging our historical distance from it. The fact that the film was screened without subtitles further heightened the abstract (and, perhaps, ironic) nature of the experience, and Vertov's occasional repetitions of the same piece of film, combined with the relentless score, gave it a strangely haunting, dream-like quality. Occasionally this evoked the work of Nyman's transatlantic counterpart Philip Glass (some of Vertov's sequences of machines were reminiscent of the Glass-scored Koyaanisqatsi) - but the effect was quite different. Instead of driving you to conclusions, it drove you to question - the very opposite of what propaganda is designed to achieve.

After Vertov the screen was raised and the event turned from accompanied screening to straight recital, with Nyman delivering a programme mostly drawn from his recent album The Piano Sings. This featured solo piano versions of some of Nyman's non-Greenaway scores, and set out to explore the more lyrical side of his work. That it certainly did, but after the first few pieces (from Michael Winterbottom's Wonderland) the plodding left hand, slow pace and simple melodies gradually started to lose their fascination, and - especially after the dynamism of the Vertov - one started to feel these pieces for what they were - scores without a film. At the end of one piece, even Nyman had to stifle a yawn. Many seemed to fall between two stools, lacking either the mesmerising starkness of Glass, Adams or Reich or the voluptuousness of Nyman's pieces for The Piano. But it was really the programme that was the problem. Individually, the slower pieces have their own distinct charm and character, but en masse they had the effect of a symphony with four consecutive slow movements - they simply lacked variation, and it was the similarities rather than the differences that ended up being emphasised.

Then came The Piano. Written as solo piano pieces from the start and with a richness some of the others lacked, these immediately transformed the mood, eliciting spontaneous applause and almost a whoop from one corner. Although Nyman is understandably uneasy with its ‘greatest hits' status, it was worth attending just for this - and never were the reasons for its popularity clearer.

After a tense delay during which the film seemingly refused to actually start (the absurd humour of which was strangely fitting) it was time for another change of pace with Vigo's À Propos de Nice. In this daft but often poignant confection, Vigo's eye takes a playful and often mischievous delight in... well, almost everything. Startled cats, drunken dancing girls, pensive statues, oversized carnival heads, overdressed tourists - all reel, dart and totter about before Vigo's hyperactive camera, which indulges every opportunity to crack visual puns or play games with scale and perspective (what appears to be one of Nice's huge palm trees turns out to be a pot plant). The carnival sequence in particular was a complete joy, with Nyman's frenetic, upbeat score perfectly suiting the slightly crazed party mood.

I have to be honest and say I rather forgot to listen to the score at this point, and simply became absorbed in the whole experience. Was that playfulness in the score, the film, or both? I couldn't tell. So, apologies to Mr Nyman for whatever I might have missed in the detail, but it would seem that in this the mission - for all to seamlessly merge in one total artwork - was fully accomplished.

Programme:

Kino Pravda 21 (Dziga Vertov, 1925) - new score

Franklyn/Jack/Debbie (from Wonderland)

Diary of Love (from The End of the Affair)

Why (from The Diary of Anne Frank)

Odessa Beach (from Man with a Movie Camera)

If (from The Diary of Anne Frank)

Big My Secret/Silver-Fingered Fling/The Heart Asks Pleasure (from The Piano)

À Propos de Nice (Jean Vigo, 1930) - new score

Writer: Toby Venables

To find out more about Cambridge Film Festival, visit:www.cambridgefilmfestival.org.uk