Search

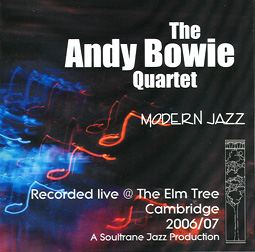

CD review: Live at the Elm Tree – The Andy Bowie Quartet

At least, that's how I remember it.

Naturally, his students thought this was pretty cool. This guy was living the Jean Paul Sarte dream (which may, to some, sound only marginally preferable to the ‘Dostoevsky dream' or the ‘Franz Kafka dream' - ie a crippling existential nightmare of self-doubt and alienation - but go with me on this). At the time, I knew nothing about jazz and had no interest in jazz recordings. I just knew I loved it then, and there. But that music wasn't about knowing. It was about being.

As the years passed - during which the semiotically challenged college underwent at least a half a dozen name changes to finally become Anglia Ruskin University - Andy Bowie moved on from his old academic stomping ground. But at the same time, with the help of the other three members of his regular quartet, he had helped to establish probably the most important regular event in the Cambridge jazz calendar: Sunday night at the Elm Tree. Now entering its ninth year, it's established a strong following among jazz devotees - and continued to mesmerise fairweather fans such as I was back way back then.

The album, recorded over various nights, presents a typical set of tunes, featuring Bowie on sax, Pete Shepherd on piano, Laurence Evans on bass and Derek Scurll on drums (Bert Schilperoort also plays drums on a few tracks) but what is most remarkable is that - somehow - it successfully conveys that most elusive of things: the live atmosphere. The recording is wonderfully crisp and immediate, not only capturing each instrument with perfect clarity but conveying the intimacy of the venue perfectly - and there's just enough background applause and bustle to take you there, without ever detracting from the music itself.

And the music itself is glorious. All musicians acquit themselves so well it seems churlish to single any out, but inevitably it's Bowie's sax that sets the tone. His sound is satisfyingly louche - witha particularly husky and melancholy tone - but there's also a startling precision to the playing. You may never have quite got Jacques Loussier's obsession with Bach, but there'd be plenty for Bach to like in this set. Likewise those who relish the live recordings of John Coltrane. And if you're already a devotee of the regular fare served up at the Elm's Sunday night jazz sessions and are looking for the takeaway version, look no further. This is a superb record of those Sundays at the Elm - the fact that it also stands as an album entirely in its own right is a testament to the quality of the musicianship and the many, many hours they've put in.

So what tunes are on the album, you ask? Does it matter? It may seem prosaic to say jazz isn't about tunes, but it's true. Tunes are about getting from A to B. This is about the going. Being in motion. If that sounds like pretentious claptrap, fine. But let's come back to that Jean Paul Sartre dream, and remember what it was that ultimately delivered Antoine Roquentin - Sartre's hero of the novel Nausea - from his existential nightmare. What gave a brief flash of meaning to the apparently meaningless world.

A jazz record, playing in a smoky café.

'For the moment, the jazz is playing; there is no melody, just notes, a myriad tiny tremors. The notes know no rest, an inflexible order gives birth to them then destroys them, without ever leaving them the chance to recuperate and exist for themselves.... I would like to hold them back, but I know that, if I succeeded in stopping one, there would only remain in my hand a corrupt and languishing sound. I must accept their death; I must even want that death: I know of few more bitter or intense impressions.'

Writer: Toby Venables (with a bit of help from J P Sartre)